The Reichstag’s beginnings

In 1871 a competition was held to design a building to house the German Parliament, after Germany’s mini states unified and became the United States of Imperial Germany. The creation of the Reichstag was however fraught with problems and was not completed until 1894.

The architect who won the competition, Ludwig Bonhnstedt, was found to be half Russian which was distasteful for the German people. Another issue was that the site which had been chosen to build the Reichstag, close to the Brandenburg Gate in the Spreebogan, bulge of the River Spree, on the Raczynski Palace grounds had not been given prior agreement by the owner, Count Raczynski. The Count, displeased he had not been consulted would not agree to the purchase of the site until after his death, which happened in 1872. The transfer was not straight forward however, it took time for the counts son to agree the purchase, eventually doing so in 1881. By this time Bonhnstedt’s design had fallen out of favour and another competition ensued. This time the competition was narrowed to German speaking architects only. In 1882 the prize was announced to two 1st prize winners Paul Wallot and Friedrich Theirsch but Theirschs’ design was not developed and the task lay with Paul Wallot.

Location of the Reichstag, Berlin, Germany Figure 1. Storming of the Reichstag 1945 Figure 2. Modern day Berlin

Figure 1

Figure 2

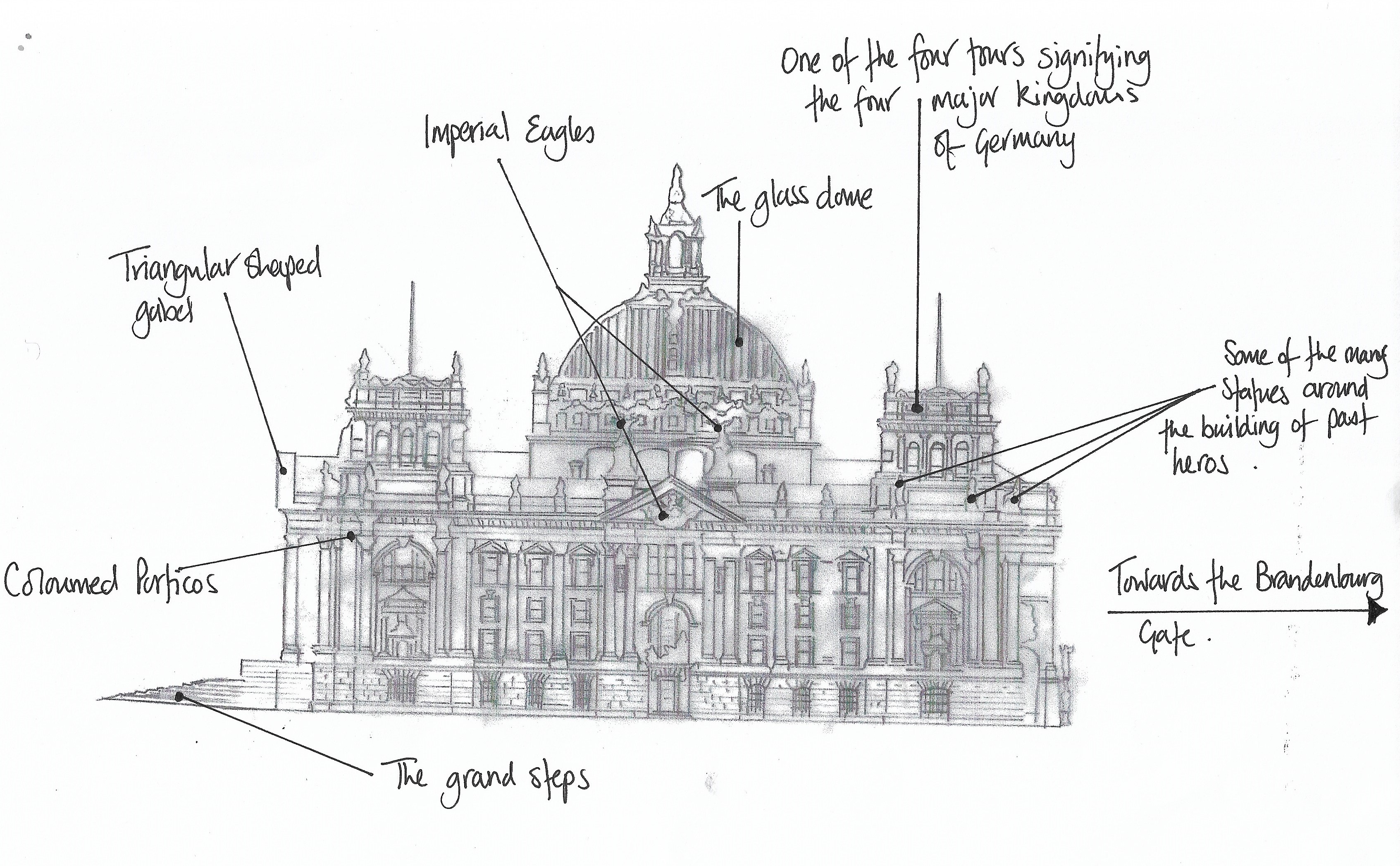

Wallot’s design came under criticism for its mix of architectural styles, which, as part of my research I myself have found myself to be true. Some sources say it is Neo-Baroque another Neo-classical another High Renaissance and classical with another stating ‘loosely Italianate in style but, jumbled together elements from a wide variety of sources including Gothic, Romanesque Baroque and Germanic’ (Foster, 2000: 40). It is indeed highly decorated with inscriptions, sculptures and reliefs. The façade comprised of columned porticos with wide steps which lead to a protruding triangular shaped gable. There are four wings to the building two inner court yards and in the centre an assembly chamber.

Wallot’s design was changed numerous times by Kaiser Wilhelm, the most contentious feature being the dome. Wallot had designed this to be above the assembly chamber to the rear of the building and to be of a stone structure. The Kaiser objected suggesting the dome should be towards the front. Not until after the Kaiser died and Kaiser Wilhelm II was in power was it agreed that the dome could be placed at the rear but at the Building Commissioners recommendation was made smaller and from glass.

Wallot had wanted Deutshcen Volke – To the German People – to be inscribed on the building but the Kaiser objected, later however, as a gesture of German unity it was inscribed in 1916 during World War I. ‘The bronze letters themselves constituted a gesture within a gesture, cast as they were from Napoleonic cannon captured at the Battle of Leipzig a century earlier’ (Foster, 2000: 40).

Wallot’s interior consisted of the chamber, a library, a writing room, a committee room, sweeping staircases and other principal rooms. Interior decoration was intensely Germanic – highly decorative with carvings, paintings, tapestries, stain glass and sculptures.

Figure 5

Figure 6

The Reichstag’s political history

The years that pursued saw political fractions and turmoil in Germany and within the Reichstag. In 1932 the Reichstag was taken control of by the Nazis and in 1933 Hitler was appointed chancellor, but without a working majority. On the left the two largest parties after the Nazis were the Socialist Democratic Party and The Communist Party. New elections were to be called on the 5th of March but on the 27th of February fire broke out rendering the Reichstag unusable. Hitler blamed the Communists for which a number were charged with arson and executed.

Prior to the fire, consideration had been given to the extension of the Reichstag and it’s surrounds to ensure it’s future suitability for parliamentary activities. In 1927 and again in 1929 competitions were held to redesign parts of the Reichstag and its surrounding areas but none came to fruition. After the fire the Nazi’s made some repairs to use it as an exhibition space and then as a war broke out again as a maternity hospital and space for military provisions.

After Berlin was badly struck by air raids in 1940 the Reichstag was used like a fortress with windows bricked up to avoid further damage to the interior and anti aircraft guns sat on top of it’s towers. But in 1945 The Red Army advanced firing on the Reichstag leaving it almost unrecognisable.

The Russian capture of the Reichstag was hugely symbolic. The Reichstag was the reason there was no Red revolution in Germany, it was also the cause of the death of Communists blamed for the fire and home of the Nazi’s who had invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. This the reason why Russian officers took great efforts to vandalise and scribe graffiti across it’s walls and columns to protest and tell Hitler what they thought of him.

The Reichstag’s modern history and developments

The Reichstag lay in ruins until 1954 when the remainder of the dome was demolished but in 1957 a start was made to the renovate the exterior. More turmoil was on it’s way however when the East German Government began the construction of a wall to prevent the loss of East Germans into the West through Berlin, The Reichstag was symbolic in the split as it sat on the very edge of the western side of the wall.

The Reichstag underwent further restoration under architect Paul Baumgarten and in 1961 opened to be used as a conference venue and museum of modern German history, without a dome and with much of it’s past stripped away. Little thought or care had been given to the historical significance of the building in Baumgarten’s designs. Foster himself comments that ‘Paul Baumgarten’s reconstruction was at odds with the original form of the building.’ (Foster, 2000: 76) Other than Fosters comments I have been unable to find much about what was thought about Baumgarten’s refurbishment of the Reichstag. The fact that there is little information and that some Reichstag research sources appear to gloss over this part of the Reichstag’s history, would suggest there is little to say about Baumgarten’s work on the Reichstag.

Things took a different course for the Reichstag after the fall of the Berlin wall and the reunification of Germany. In 1991 it was agreed that Berlin should once again be home to the German parliament and later agreed that the Bundestag be housed in the Reichstag. Foster was appointed in 1993 but prior to Fosters restoration of the Reichstag an art project, which originated in 1971, came to fruition when artists Christo and Jean Claude wrapped the Reichstag in more than a million square feet of fabric rendering the large wounded bulk of a building ‘light, almost delicate. It takes on an ethereal beauty, and looks as if it could float away into the silvery, cloudy Berlin sky.’ (Goldberg, 1995)

Figure 9

Restoring the Reichstag: historical, political and cultural design decisions

In contrast with Baumgarten’s reconstruction Foster appears to have taken all of the Reichstag’s historical past into consideration. The new Reichstag was to be a symbol for not forgetting the past but for moving on, a symbol of Germany’s future, togetherness, openness and without boundaries. To communicate this the brief had a robust ecological agenda; the use of daylight, transparency and to provide public access to create a truly democratic building. Foster also focused on the Bundestag itself understanding the way it worked and what it’s needs were, so much so Foster proposed that the building could provide space for other political parties, rather than house them else where, as was the intention. He also proposed space for the press. His understanding of the buildings history, it’s future and his knowledge of German parliament won him the competition.

Much of what Wallot had designed and built had been destroyed but Foster admired Wallot’s ‘well-planned and logical building’ compared to Baumgarten’s which ‘was at odds with the original form of the building’. (Foster, 2000: 76) But when peeling away the surfaces Foster uncovered some of Wallot’s Reichstag as well as the graffiti left by the Soviet Soldiers. Foster was determined that these elements should stay as a true living history. When this was agreed Foster felt Germany had proven it was now a truly democratic culture.

Foster respected the old building during the restoration, retaining Wallot’s original floor levels, qualities of his planning grid and restoring some architectural features. Where old meets new the cross over is clearly denoted.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Foster also had to take the building into the future, which he did so by eliminating as many ‘secret’ spaces as possible and opening the compartmentalised building Wallot had created. The most significant change to the building was cutting through the building from top to bottom, mainly over the chamber to expose the building to light and views and to erect the cupola. A Cupola which is open to the public with it’s surrounding public roof terrace. The building is split into separate areas for The President, MPs, administration, press and public, some areas of course cross over. It was important that the building did not portray a them-and-us attitude, Foster’s design ensures this is not the case. Everyone comes through the same front door, first alighting the grand steps leading to a 30-meter high foyer. The chamber was designed to feel intimate so that when only a small group of MPs are attending it does not provide a sense of dominance. Chamber seating and public tribunes are closely arranged so the public can attend to listen to debates and not feel disconnected from the proceedings while Mezzanine connecting bridges allow views to look down into the east foyer which at times is used for formal events. On entering the building the public can see directly through a glass partition where the Bundestag sits including the president, the chancellor and other political leaders. Public, politicians and press can mix and relax on the roof terrace and restaurant.

Figure 12

Figure 13

The cupola, which was developed over time, was designed not only to bring daylight into and through the building but to ventilate it too. For Foster the cupola was ‘a marker on the Berlin skyline, communicating themes of lightness, transparency, permeability and public access that underscore the project’. (Foster, 2000: 87). It also provides views over Berlin allowing you to see the significance of the modern day Reichstag’s positioning, with the Tiergarten and new Chancellery Buildings to the west, the historical quarter to the east, Potsamer Platz’s new commercial towers to the south and in front, the Brandenburg gate.

The ecological brief was further upheld – the building does not burn fossil fuels but vegetable oil which through a process of cogeneration produces electricity. Excess heat is stored below the ground and through a variety of process can be used to heat the building or produce cold water. 94% less emissions of carbon dioxide are produced, in a building which works as a small power station producing more energy than it uses.

Conclusion

Understanding the history of the Reichstag has been fascinating, the historical significance of the building is huge. From its beginnings it was adorned with stained glass, art work and statues to depict the unity Germany had come to know at that time. It’s 4 towers signifying the four kingdoms of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Wurttemberg and statues created to epitomise defence against evil, such as dragon slaying and eagles wining the fight with snakes. There too were symbols of trade, agriculture and art, prosperous under the German empire. But the scars of fire and war are as much depictions of history as the statues and art work. The fact that the building, although wounded, battled on and stood the test of time is hugely symbolic for what Germany and it’s people have been through. With what I have come to know about the building and its past I believe it was truly the right thing for Parliament to return to the Reichstag and not just create a monument or museum but to continue its story and to give it new life. To keep the graffiti and memories of its troubled passed is an honorable thing to do and to invite in the public and let them see the past as well as the future in this magnificent building seems truly progressive. Foster I feel has managed to make a hugely sustainable building, to renew and reinvigorate it in exactly the way the German people wanted while creating a fantastic piece of architecture that people from all over the world can take the opportunity to enjoy and learn from.

Bibliography

Images

Figure 1. Storming the Reichstag [Map]http://www.armchairgeneral.com/rkkaww2/maps/1945W/1BF/Berlin/756RR_assault_45.jpg. (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Figure 2. Ariel photograph of the Spree (2010) [Photograph] https://maprhizome.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/berlin-aerial-plan1.jpg. (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Figure 3. Internal Reichstag [photograph]https://i.pinimg.com/736x/6e/6c/4d/6e6c4d988918f5f1966853b97721d987–reichstag-potpourri.jpg (Accessed 02.03.19)

Figure 4. Internal Reichstag [photograph]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f8/Bundesarchiv_Bild_116-121-007%2C_Mitglieder_des_Deutschen_Reichstag.jpg. (Accessed on 03.03.19)

Figure 5. To The German People[photograph]https://c2.staticflickr.com/6/5131/5398562040_f2024639b5_b.jpg. (Accessed on 03.03.19)

Figure 6. Internal Reichstag [photograph]http://slideplayer.com/slide/10990123/39/images/5/Interior+of+the+Bundesrat+(1899-1903).jpgate (Accessed on 02.03.19)

Figure 7. Reichstag [photograph]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e6/Berlin-Reichstag_1929.jpg. (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Figure 8. Construction of the Berlin Wall [photograph]http://theimageworks.com/pub/nn032/berlinwall/images/prevs/prev4.jpg. (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Figure 9. Wrapped Rechistag (2017) [photograph]https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/feb/07/how-we-made-the-wrapped-reichstag-berlin-christo-and-jeanne-claude-interview. (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Figure 10. Reichstag restored Graffiti [photograph] http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-58HR-uqjhEM/Tj2JNsDhFTI/AAAAAAAAAIM/bLa-hVCiF38/s1600/IMG_5484.JPG. (Accessed 02.03.19)

Figure 11. Reichstag interior [photograph]https://arcretrofitting.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/img12.jpg. (Accessed on 02.03.19)

Figure 12. Reichstag chamber [photograph]https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/reichstag-new-german-parliament/#gallery. (Accessed on 03.03.19)

Figure 13. Reichstag views [photograph]https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/reichstag-new-german-parliament/#gallery. (Accessed on 03.03.19)

Sources

Berlin.de. (2019). Reichstag. berlin.de. At: https://www.berlin.de/en/attractions-and-sights/3560965-3104052-reichstag.en.html (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Goldberger, P. (1995). Christo’s Wrapped Reichstag: Symbol for the New Germany. Nytimes.com. [online]At: https://www.nytimes.com/1995/06/23/arts/christo-s-wrapped-reichstag-symbol-for-the-new-germany.html (Accessed on 01.03.19)

History Learning Site. (2019). The Reichstag Fire of 1933 – History Learning Site. [online] At: https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/nazi-germany/the-reichstag-fire-of-1933/ (Accessed on 01.03.19)

Foster, N. (2000). Rebuilding the Reichstag. Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press.

http://www.fosterandpartners.com, F. (2019). Reichstag, New German Parliament | Foster + Partners. Fosterandpartners.com. At: https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/reichstag-new-german-parliament/ (Accessed on 03.03.19)